Distillation of molasses creates a by-product called VINASSE- Concentrated Molasses Stillage at the rate of at least 13 litres per litre of Éthanol.

Publicité

This by-product is mixed with granular fertilisers to produce liquid fertilisers utilised solely by the Corporate Sugar sector thereby reducing their cane production cost. If this saving is shared with other cane planters, they can also reduce their costs and be encouraged to come back to cane cultivation.

The JTC the MCIA have guesstimated a viable income to a small cane planter to be Rs 17,000/ton sugar. The main flaw of this argument is that sugar can no longer be used as a yardstick to determine planters’ revenue. In 2017 we are exporting our sugar at Rs 11,300 net per ton (Rs 11 per kg). But our local consumers have to pay for imported sugar at Rs 36,000 per ton (Rs 36 per kg). Sugar imported for uses other than refining is being charged with a custom duty of 15% currently but the JTC is proposing to increase this to 100%. Why is the price of sugar kept artificially high on the local market? How will Government implement its “Sugar Based Agro –Industry Framework with an import duty of 100%?

The reform of the sugar industry, the centralisation process and the investment in refining capacity facilitated the production and sale of WRS ready for consumption and for Special Sugars. This was supposed to reduce costs and to bring more revenue to the planters than from the sale of raw sugar but the sale of the WRS has failed to generate the additional revenue initially forecasted. Small planters are still being paid on raw sugar basis (Rs 11,300/Mt sugar) and have not benefitted from the value addition/ premium resulting from the sale of WRS and special sugars. Special sugars are 40% to 85% more remunerative than WRS. The accounts of the MSS (2014-2015) reveal that WRS sells at Rs 13,642/ton whereas special sugars fetch Rs 24,986/ton.

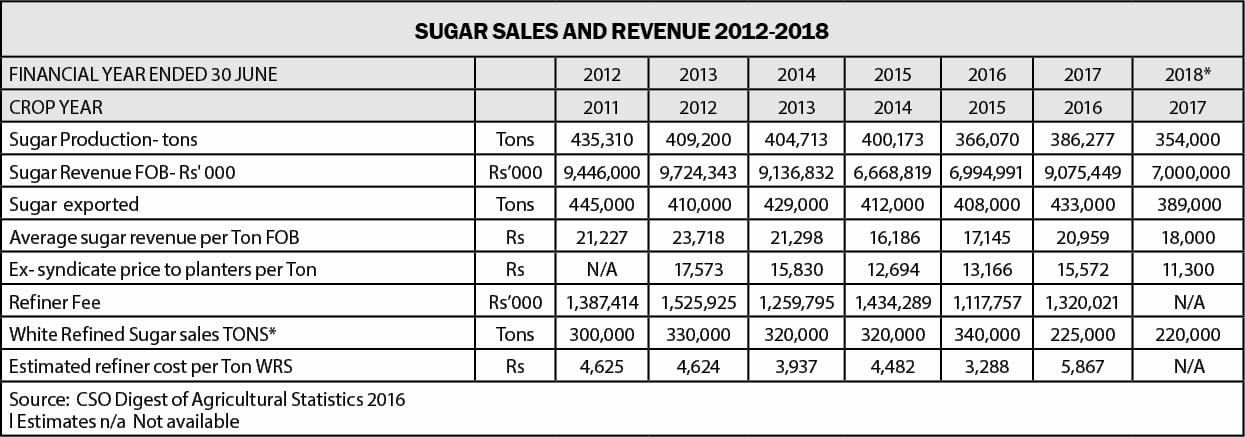

It is reported that the revenue of special sugars will exceed Rs 30,000/ton for the 2017 crop. The additional income from WRS - Rs 4,400/ ton sugar are paid to the millers directly over and above the cost of cane processing under the age-old sugar apportionment ratio of 78/22 which amounts to about Rs 3,300 per ton sugar. The processing cost and refining cost to the cane grower is Rs 7,700 or USD 220 /ton sugar when the world sugar price of WRS is USD 346/ton (OECD library). A close look at the accounts of the MSS will confirm the aforesaid. The MSS paid Rs 1.3bn (see table 2) to refiners for the 2016 crop. It is unacceptable that small cane growers continue to bear additional refinery cost given that the capital expenditure on the same have been fully recovered by 2015.

The 78/22 apportionment ratio was further in force (year 2000) when the country had more than 14 sugar mills. The centralisation of milling factories into only four units coupled with the reduction in labour force have led to economies of scale and cost reduction, which in itself should have triggered revision of the rate to 80/20 at least. But this has not been done once again to the detriment of the small cane growers. We can therefore safely ask as to who is the real risk taker in this industry. Small planters are being made to pay for the hidden costs of refinery and special sugars, which impacts their income adversely. They are bearing all the risks and losses whereas corporate planters/millers reap all the rewards and perks at zero risk. The smaller the planter the greater the suffering. The international price of WRS is not expected to be above US$ 350 per ton up to 2026 (per OECD library). No wonder that small planters are dying a slow death. With hindsight, we can question the very strategy of investing into refineries for WRS.

This being said, it is time to have an open book policy in the milling and refinery operations. Nobody, not even the Government knows what is the exact cost of producing a ton of Sugar or the cost per kWh of electricity generated by the IPPs out of bagasse and this despite the existence of so many regulators. Full absorption costing is being utilised by the millers/refiners/IPPS in their claims to the MSS and the CEB whereas the production system is vertically integrated and runs on an incremental/ marginal cost basis. Therefore, there is plenty of room to provide for adequate income to all planters.

Equity participation in cane clusters

Since we are speaking of the cane industry, Government must forcefully implement the December 2007 agreement between itself and the MSPA to grant 35% equity participation directly to the planters and workers community in the whole cane cluster and it has to reactivate the “Cane Democratisation Fund” set up for this purpose. The agreement also covered the allocation of 2,000 acres of land to Government for social housing and food security out of which nearly 1,000 acres have still not been vested into the state.

Electricity cogeneration & electricity tariffs

According to J.M. Paturau (1989), 450 kWh electricity can be produced per ton of mill-run bagasse. With technological progress over the years, some 550-600kWh of electricity can now be produced per ton of mill run bagasse and at a much lower cost - with power plants operating around 82 bars and equipped with matching condensing-extraction turbo-alternators. According to Dr K. Deepchand’s paper on “Sugar cane Bagasse Energy Cogeneration-2005,” from an average of 13 kWh of electricity produced in 1988 per ton of cane, the figure rose to 125kWh /ton cane in 2004 (at CTBV) with a power plant operating at around 82 bars. By updating these figures, we can safely estimate by how many kWh the production has gone up per ton cane since then. Dr K. Deepchand further estimates that some 800 GWh of electricity can be exported to the grid compared to the actual 350 GWh and to the 510 GWh proposed by the JTC.

Way back in 1989 J. M Paturau had already worked out the approximate cost of electricity produced from mill run bagasse to be approximately US$ cents 6 to 8per kWh with a bagasse price of US$15/ton. Today, despite all the technological progress realised to produce more electricity from a reduced cane output and despite the fact that IPPs are using Bagasse free of cost, the IPPs are still billing the CEB up to 8 US$ cents (Rs 3.00) per kWh and the JTC is now proposing to bill Rs 6.80 (19.40 US$ cents) per kWh.

All this has to be paid by the consumers. Had the regulators compared the cogeneration cost of electricity from bagasse with countries like Brazil, India and South Africa, they would have certainly known the optimal production cost per kWh and eventually determine a reasonable tariff per kWh for the benefit of the consumers, the IPPs and the cane growers. This is why there is an urgent need for a proper audit of the actual cost of generation of energy per kWh from bagasse.

Harvesting and field management

One of the ways to help the cane growers is to maximise land use through the utilisation of plant and equipment in harvesting and field maintenance. The various field management and land preparation programmes devised over the decades to alleviate the problems of small cane planters have not yielded the desired results due to the bureaucracy involved in those schemes (LAMU, FORIP & SPRP). If Government wants small planters to come back to cane cultivation the support institutions have to be more proactive and innovative. The main problem of small planters is harvesting, loading and transportation of cane to the mills.

The MCIA and the sugar mills must be able to organise these operations for cane growers falling in every factory area to enable these cane growers also to benefit from economies of scale in field operation. The MCIA should invest in an adequate number of efficient loading equipment that operates on the same basis as the miller/planter in areas where mechanisation is not possible. It is not a big feat to plan this operation given that we are now speaking of only 13,000 small planters/’metayers’ cultivating some 15,000 ha of land. On the contrary, this measure coupled with increased income from bagasse, molasses and electricity may bring some 10,000 ha back under cane cultivation.

Labour & compensation

The direct labour component of the sugar cane industry has fallen from 45,000 in 2001 to just 7,000 owing to the centralisation of milling operations and mechanisation of most field operations largely funded by the EU and the State.

The success of the sugar industry has mainly been achieved through the endless contribution and sacrifices of labourers and artisans who, back in 1956, were working for a salary of Rs 1.40 per day. No cost cutting scheme can be approved if it goes against the interest and the acquired rights of the sugar cane workers and artisans. The JTC is proposing to reduce labour cost by 40%, to limit the NPF contributions of Employers to 6.5% instead of the 10.5% paid by all other employers, especially the SMEs, who are operating without any protection net. The RNC is also proposing to include labour services to the cane sector on the list of essential services like security, fire, and health, which is a blatant attempt to curtail the right to strike.

The SIE Act 2016 moved bagasse and molasses from the exempt supplies to the ZERO rated supplies - the end result of which would be a saving of 15% on the cost of inputs used by the corporate sector. Now the JTC is also advocating exemption from payment of VAT on land conversion rights for corporate planters. On the other hand, the JTC is proposing to increase land conversion tax from Rs 3.5m to Rs 5.5 m / ha to curb land abandonment by other planters. The Corporate sugar sector has been benefiting from overgenerous fiscal handouts over the years to the detriment of tax payers. All these benefits have been claimed on the shallow grounds of preserving jobs, protecting the small planters and maintaining the competitiveness of the industry.

SUGAR SALES AND REVENUE 2012-2018

The way forward

The survival of the Cane Industry is in the interest of one and all because of its socio-economic and environmental impacts on the economy. This is a partnership where all the partners must act in a transparent and equitable manner. It is well known that the strength of a chain is based on the strength of its weakest link. In the cane industry, the weakest links are the workers and the small planters. It is also a fact that any organisation cannot be too big not to fall. Therefore this boat cannot go far unless there is a common will to row together and in the same direction. The proposals made above can easily provide an income of nearly Rs 2,000 per ton cane to all cane growers. To summarise, therefore, the following urgent steps have to be addressed:

1. To set aside the report of the JTC outright.

2. To implement the 35% Equity Participation agreed in 2007 (Not through the SIT) of workers and small cane planters/ metayers in the whole cane cluster by reviving the “Cane democratisation Fund.

3. To review the 78/22 apportionment ratio to 80/20. Planters should not be made to pay for the hidden costs of refinery and special sugars, electricity generation, molasses and bioethanol.

4. To concentrate on the production, marketing and sale of special sugars which are 40%-85% more remunerative than WRS.

5. To revamp the MSS and review its composition and functioning in order to transform it into the Mauritius Cane Syndicate to cater for the promotion and sale of the cane and all its by-products.

6. To fix the bagasse income to its actual weight instead of tons sugar accrued basis. An initial price of Rs 1,500 per ton of bagasse will be a correct beginning provided that the small planter is paid in Toto for his bagasse output and not on surplus bagasse only.

7. The Bagasse Price Transfer Funds must be solely dedicated to the small planters.

8. Molasses income of planters should be linked to the value added from conversion into rum and ethanol and the planters should also receive a fairer share from the direct export of Molasses by Alcohol & Molasses export Ltd (AMEL).

9. Small planters must also receive their fair share of income from the sale of WRS actually distributed to millers only.

10. Small planters must obtain their fair share of income from electricity generated from their bagasse.

11. Workers’ acquired rights to pay, pensions and other accruing benefits must be protected at all costs including their pension rights and the rights to strike. The recommendations of the JTC to layoff labour and to curtail the rights of sugar industry workers have to be strongly resisted and set aside.

12. The appointment of an independent international team of experts (not Landell Mills of Ireland please!!!!!) to review the cane industry in a holistic manner and to ascertain the actual cost of production of sugar, ethanol, electricity and rum and other cane by-products with a view to redistribute incomes generated from the cane Industry on a more transparent, just and equitable basis.

13. Support institutions and regulators must effectively work in the interest of all the cane growers and not only the corporate sugar segment. The MCIA can start by controlling sugar, molasses and scums extraction countrywide paying special attention to extraction rates and manipulations. It should also invest in cane loading equipment’s and facilitate transport of small cane growers cane to the mills on a competitive basis.

Notre service WhatsApp. Vous êtes témoins d`un événement d`actualité ou d`une scène insolite? Envoyez-nous vos photos ou vidéos sur le 5 259 82 00 !

![[Document] Réforme électorale : découvrez les propositions du gouvernement](https://defimedia.info/sites/default/files/styles/medium/public/reform_electorale_document.jpg?itok=i-XvATtS)